In the 1980s, the manufacturing industry underwent workflow changes, and the software industry later embraced these practices with the Agile and DevOps methodologies. The Toyota Production Systems (TPS), for example, has majorly inspired Agile practices in software.

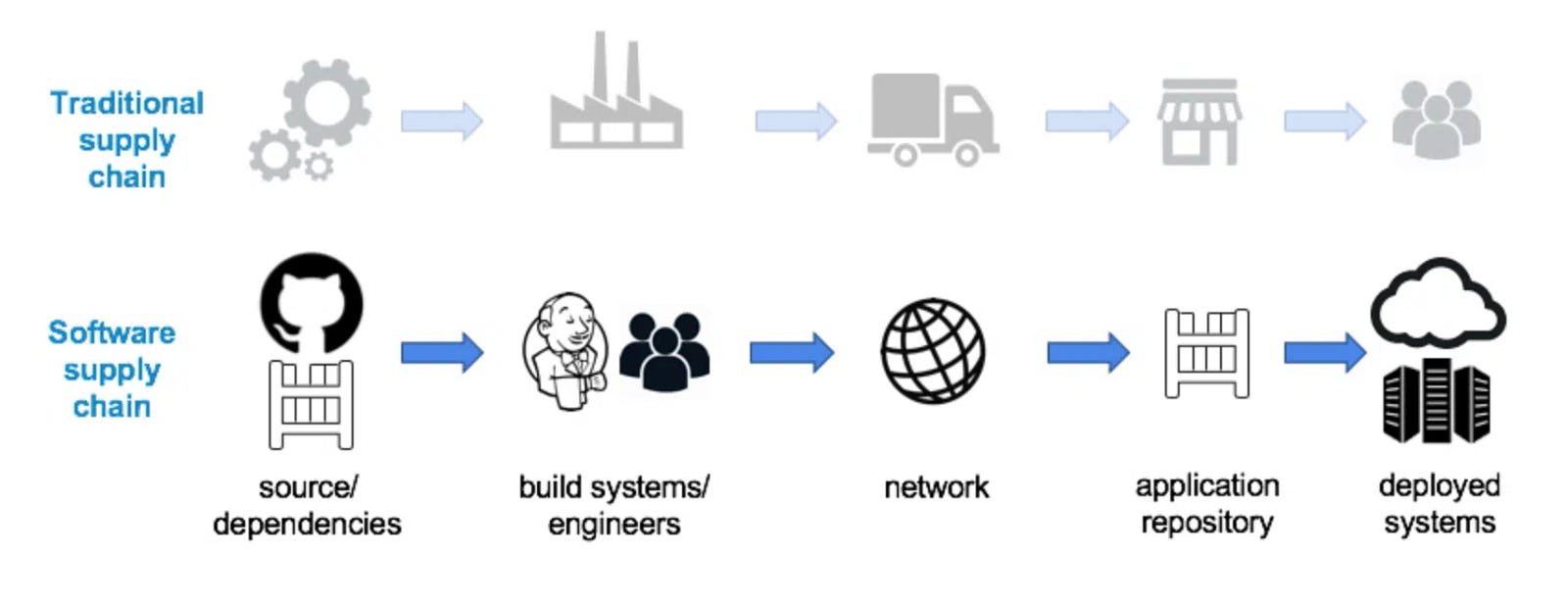

As modern software supply chains grow increasingly complex, their attack surface inherently increases too. Therefore, technology now continuously seeks to adapt manufacturing supply chain practices to improve software lifecycles.

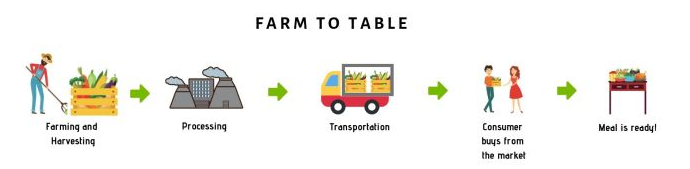

Farm to Table

If we look at the food industry for example, a considerable effort is being put around “farm to table” food safety; Between the farm and the dinner table, numerous threats exist where disease-causing organisms and other food safety hazards can potentially infiltrate the food supply chain.

In the context of software supply chain, we have similar threats where a software can be maliciously altered during the delivery pipeline.

Since the security of a supply chain is defined by its weakest link, any compromise that occurs throughout the steps of a software pipeline might result in malicious artifacts delivered to the end-users. That’s why it’s important to secure the software supply chain end-to-end.

In this article we are going to tackle different software supply chain misconceptions, explain about supply chain integrity and finally present a cryptography-based solution for securing the end-to-end supply chain of a software product, using a research-backed framework called in-toto .

Supply Chain Integrity

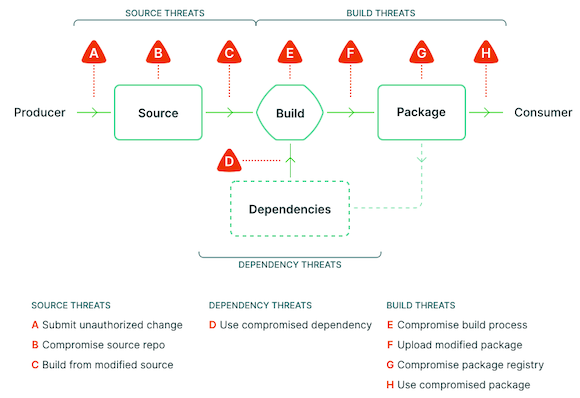

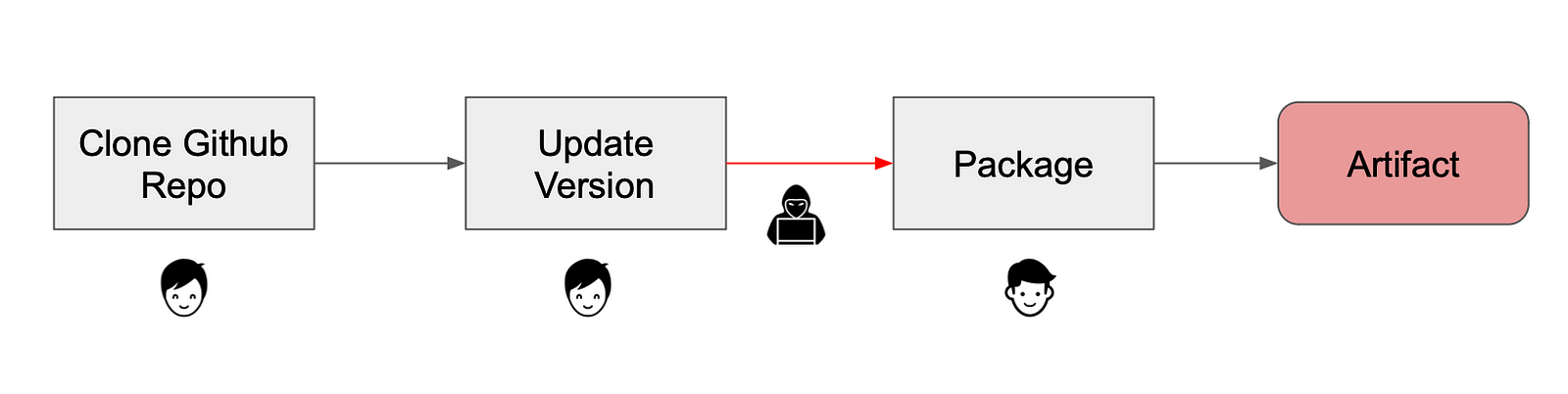

The following diagram depicts the potential attack vectors in which the software pipeline can be compromised:

As we can see, the software supply chain is exposed to many potential threats, across all of its stages. These threats are more focused on the compromise of the build and release pipeline. If attackers can control any step in the pipeline, they might be able to modify the output of the process for malicious purposes.

Supply chain integrity refers to protection against tampering or unauthorized modification at any stage of the software lifecycle. In its most basic scenario - an attacker hacks into the build server and inserts a malicious code, just right before the software source code is built and packaged.

Attestations over Signatures

Apparently, SolarWinds did apply code-signing in their supply chain and the signing certificate was not compromised when signing the tampered code.

What seems to have failed at SolarWinds was the integrity of the supply chain. Specifically, there was no coupling between the source code repository and the code signing system. If the code signing system has no knowledge about what code it signs, then the signing act becomes less effective.

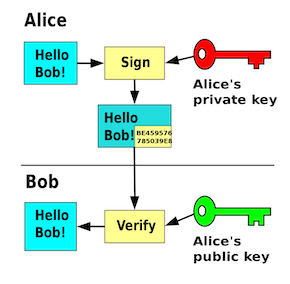

The challenge is how can we determine which source code was used in the code signing? While we might assume it originated from the code repository, the code’s signature does not offer any confirmation of this.

In other words, if the signature is cryptographically valid, it confirms that the holder of the private key used that key to sign the artifact. Nothing less and nothing more!

However, this validation alone does not verify the users’ intent to sign the artifact or their intention to make particular assertions about it.

More implicit, less explicit

According to SLSA, one of the key principals of supply chain security is to “Prefer attestations over inferences”:

Require explicit attestations about an artifact’s provenance; do not infer security properties from a platform’s configurations.

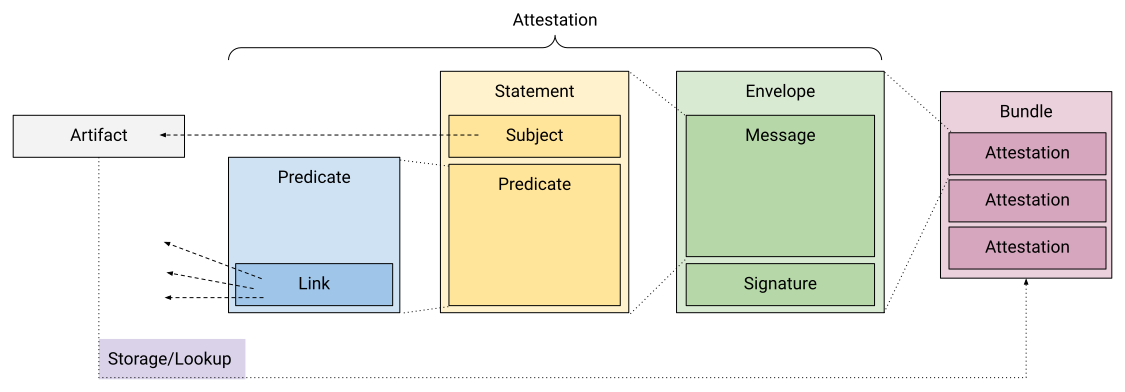

A software attestation is an authenticated statement (metadata) about a software artifact or collection of software artifacts.

We can somehow think of signing as generating an attestation, but this attestation is essentially empty or provides minimal explicit information. All details regarding how the software was constructed are solely implied from the act of signing itself.

This is where more advanced systems become essential. Instead of directly signing an artifact, developers create a document, that encapsulates their intent behind signing the artifact and any specific claims associated with the signature.

This document, once cryptographically signed, will create an attestation. The attestation will later allow end-users of the artifact to retrieve trusted claims and evidences about the artifact.

Piecemeal vs. Holistic Approach

As we already explained, signatures are not bullet-proof. Moreover, if we explore different supply chain security strategies, they are usually limited to securing each individual step within it. For example:

- Git commit signing is used to control which developers can modify the source code.

- Reproducible builds enable multiple parties to independently build software from its source and confirm they obtain identical results.

And of course there is an endless offering of frameworks and tools that protect software delivery in different ways. The problem is that these solutions help to secure individual steps in the supply chain. They are essentially piecemeal measures in the supply chain security process.

But as we observed in the SolarWinds attack example, such security measures can be undone if attackers can modify the output of a step, before it is fed to the next one in the chain.

Therefore, what we need is a more end-to-end approach that allows to verify the integrity of the supply chain holistically.

Introducing In-toto

It all goes back to the 2019 research paper “in-toto: Providing farm-to-table guarantees for bits and bytes”. The researches behind this paper, reported studying 30 major supply chain breaches. In-toto, they concluded, would have prevented between 83% and 100% of those attacks. Flash forward a year later, the SolarWinds attack has occurred and caused many organizations to re-think the security of their software supply chain integrity.

A year after the attack, it was reported that a cybersecurity system called in-toto might have protected against this attack:

The software company SolarWinds unwittingly allowed hackers’ code into thousands of federal computers. A cybersecurity system called in-toto, which the government paid to develop but never required, might have protected against this.

What is in-toto?

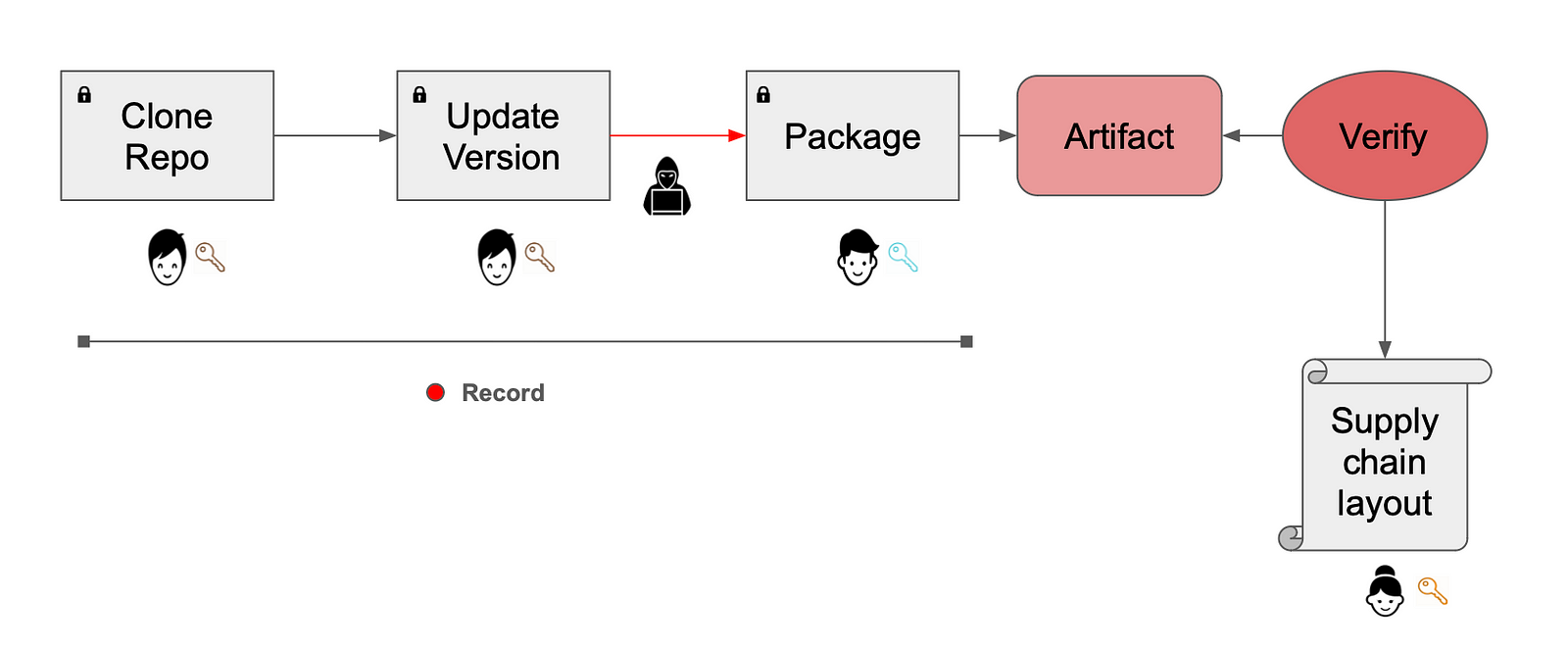

in-toto is a framework to secure the integrity of the supply chain. It enforces the integrity of a software supply chain by gathering cryptographically verifiable evidence about the chain itself. To achieve this, in-toto relies on the following main principles:

- Layout integrity: Verify that the pipeline is executed as specified, with no steps added, removed or reordered.

- Artifact flow integrity: Verify that artifact are not altered in-between steps.

- Step authentication: Only authorized parties can actually perform the pipeline steps.

In-toto is composed of the following users and steps:

- Supply chain owners define a “layout” of the software supply chain and cryptographically sign it using their private key.

- Project functionaries attest the executed steps in the supply chain by generating cryptographically signed “links” (evidence) that contain metadata about the steps.

- End-users verify the final artifact by analyzing the links to ensure that they meet the constraints set in the layout.

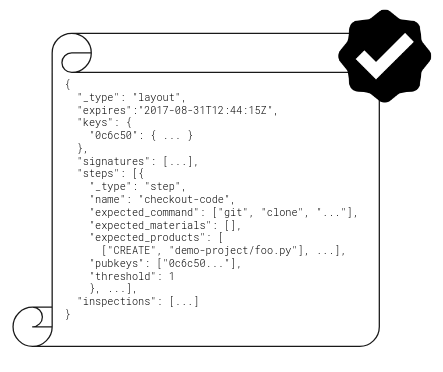

in-toto Layout

The first step is to define the layout. The project owners define the build and release pipeline through a sequence of steps outlined in a layout. Each step specifies the parties authorized to perform it, identified by their public keys, and can include constraints dictating its permissible actions (e.g., restricting modifications on specific files).

Each step in the layout can detail its expected materials (input), expected products (outputs), expected execution command, a threshold for the number of independently signed pieces of data required for verification, and the public keys of the parties authorized to sign its metadata.

The final segment of the layout includes inspections, outlining checks for a end-users to validate the integrity of the delivered artifact.

Once the layout is defined, it’s cryptographically signed by the project owners using their private key.

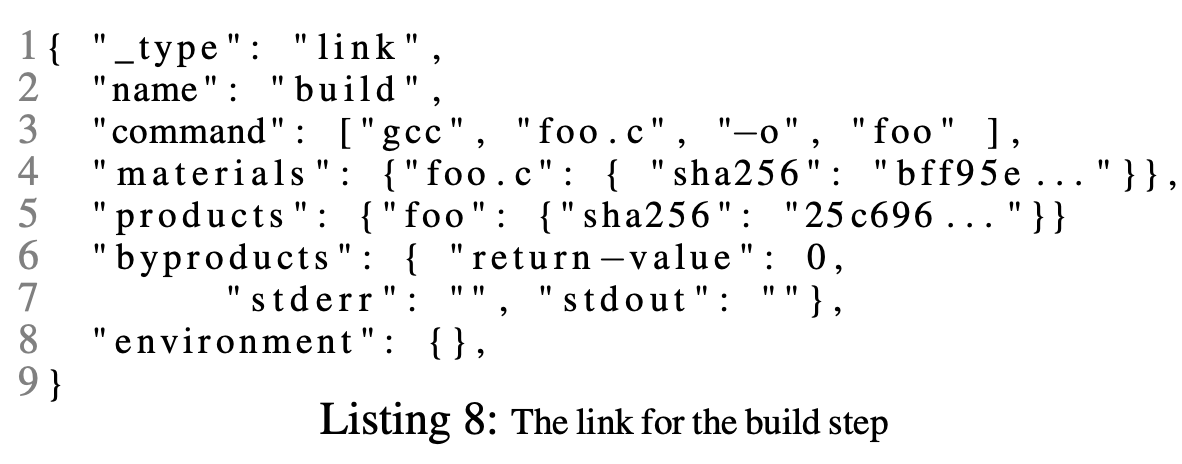

in-toto Attestations (Link Metadata)

Throughout the pipeline execution, metadata linking steps are generated and signed using the private key of the functionary responsible for each step. These links are the signed evidence of the step. These links are generated by recording the commands execution and hashing the inputs and outputs of the steps in the pipeline. The link metadata is then signed using the private key of the step’s functionary.

The link metadata recorded from each step can be verified to ensure that all steps were carried out appropriately in the manner specified by the layout (layout integrity) and by the correct parties (step authentication).

The layout and collection of link metadata establish strong connections between the inputs and outputs of each step in the chain, thereby preventing tampering between steps. An attacker cannot disrupt two consecutive steps in the supply chain because, during verification, the hash of the products field in the link from the first step will not match with the hash of the materials field in the link for the following step (artifact flow integrity).

Final Product Verification

To ensure the authenticity of the final product, the end-user should receive the final software artifact along with the:

- Signed Supply chain layout

- Signed Link metadata files

- Public key of the project owner that signed the layout

By verifying the final product using the signed layout and link metadata, the end user ensures that the software has not been altered and confirms that all steps were executed according to the specifications in the layout. The pseudo-code below describes the verification process of the final product:

function VERIFY_FINAL_PRODUCT

Input: layout; links; project_owner_key

Output: result: (SUCCESS/FAIL)

// verify that the supply chain layout was properly signed

if not verify_signature(layout, project_owner_key) then

return FAIL

// Check that the layout has not expired

if layout.expiration < TODAY then

return FAIL

// Load the functionary public keys from the layout

functionary_pubkeys = layout.keys

// verify link metadata

for step in layout.steps do

// Obtain the functionary keys relevant to this step and its corresponding metadata

step_links = get_links_for_step(step, links)

step_keys = get_keys_for_step(step, functionary_pubkeys)

// Remove all links with invalid signatures

for link in step_links do

if not verify_signature(link, step_keys) then

step_links.remove(link)

// Check there are enough properly-signed links to meet the threshold

if length(step_links) < step.threshold then

return error("Link metadata is missing!")

// Apply artifact rules between all steps

if apply_artifact_rules(steps, links) == FAIL then

return FAIL

// Execute inspections

for inspection in layout.inspections do

inspections.add(Run(inspection))

// Verify inspections

if apply_artifact_rules(steps + inspections, links) == FAIL then

return FAIL

return SUCCESS

in-toto in Action

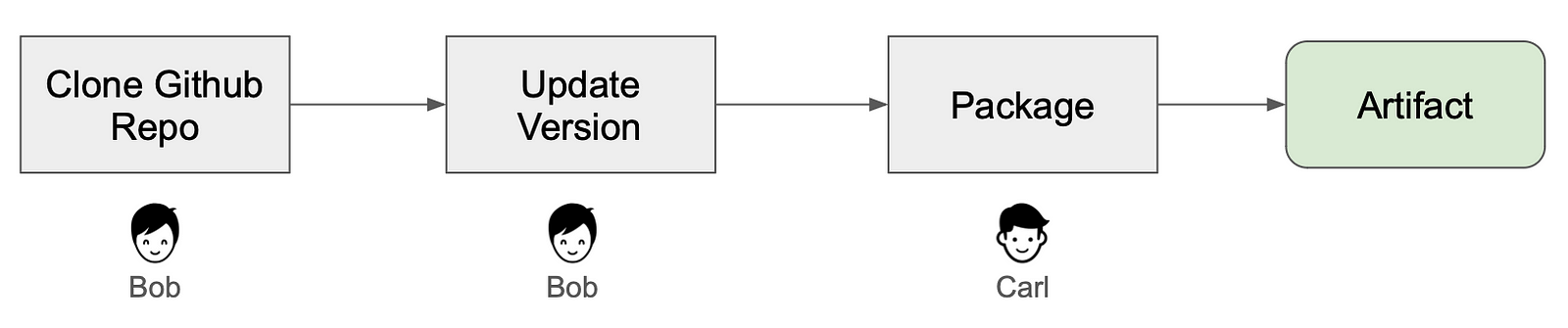

Let’s continue with the SolarWinds attack example that we’ve presented earlier and try to simulate it (in the simplest manner of course) with in-toto. We will demonstrate how in-toto will detect that a malicious code was injected into the source code, just before it is built and packaged.

We introduce a simple supply chain that includes the following steps:

- Bob works as a developer on the project .

- Carl handles the software packaging.

- Bob usually modifies the source code of the project and delivers it to Carl for building and packaging it in the build server.

- Alice is the project owner who oversees the entire supply chain.

In the context of in-toto’s terminology:

- Alice acts as the project owner, responsible for creating and signing the software supply chain layout with her private key.

- Bob and Carl act as project functionaries, executing the steps defined in the layout within the software supply chain.

Defining and signing the layout

First, we will take the role of the project owner Alice, and start defining the software supply chain layout, according to in-toto’s layout specification. The following Python code snippet will programmatically create an in-toto layout and add Bob’s and Carl’s public keys in the layout:

from securesystemslib import interface

from in_toto.models.layout import Layout

# Fetch and load Bob's and Carl's public keys

# to specify that they are authorized to perform certain step in the layout

key_bob = interface.import_rsa_publickey_from_file("../functionary_bob/bob.pub")

key_carl = interface.import_rsa_publickey_from_file("../functionary_carl/carl.pub")

layout = Layout.read({

"_type": "layout",

"keys": {

key_bob["keyid"]: key_bob,

key_carl["keyid"]: key_carl,

},

"steps": [{

# step1: clone github repo

"name": "clone",

"expected_materials": [],

"expected_products": [["CREATE", "demo-project/foo.py"], ["DISALLOW", "*"]],

"pubkeys": [key_bob["keyid"]],

"expected_command": [ "git", "clone", "https://github.com/in-toto/demo-project.git" ],

"threshold": 1,

},{

# step2: update version

"name": "update-version",

"expected_materials": [["MATCH", "demo-project/*", "WITH", "PRODUCTS",

"FROM", "clone"], ["DISALLOW", "*"]],

"expected_products": [["MODIFY", "demo-project/foo.py"], ["DISALLOW", "*"]],

"pubkeys": [key_bob["keyid"]],

"expected_command": [],

"threshold": 1,

},{

# step3: package source code

"name": "package",

"expected_materials": [

["MATCH", "demo-project/*", "WITH", "PRODUCTS", "FROM",

"update-version"], ["DISALLOW", "*"],

],

"expected_products": [

["CREATE", "demo-project.tar.gz"], ["DISALLOW", "*"],

],

"pubkeys": [key_carl["keyid"]],

"expected_command": [ "tar", "--exclude", ".git", "-zcvf", "demo-project.tar.gz", "demo-project" ],

"threshold": 1,

}],

"inspect": [{

"name": "untar",

"expected_materials": [

["MATCH", "demo-project.tar.gz", "WITH", "PRODUCTS", "FROM", "package"],

["ALLOW", ".keep"],

["ALLOW", "alice.pub"],

["ALLOW", "root.layout"],

["ALLOW", "*.link"],

["DISALLOW", "*"]

],

"expected_products": [

["MATCH", "demo-project/foo.py", "WITH", "PRODUCTS", "FROM", "update-version"],

["ALLOW", "demo-project/.git/*"],

["ALLOW", "demo-project.tar.gz"],

["ALLOW", ".keep"],

["ALLOW", "alice.pub"],

["ALLOW", "root.layout"],

["ALLOW", "*.link"],

["DISALLOW", "*"]

],

"run": [ "tar", "xzf", "demo-project.tar.gz" ]

}],

})

A brief explanation of the layout above:

- In the

keyssection, we define the public keys of the functionaries (Bob and Carl). - In the

stepssection, we orderly define each step in the layout. For each step we define the expected inputs, outputs and commands when executing the step in the supply chain. Also for each step we associate the public key of the permissible functionary (Bob or Carl). - In the

inspectsection, we describe which inspections need to be done when verifying the final product against the layout and the link metadata.

Once the layout is created, we should sign it with Alice’s private key and dump its output into a file:

from securesystemslib import interface

from securesystemslib.signer import SSlibSigner

from in_toto.models.metadata import Envelope

# Load Alice's private key to later sign the layout

key_alice = interface.import_rsa_privatekey_from_file("alice")

signer_alice = SSlibSigner(key_alice)

metadata = Envelope.from_signable(layout)

# Sign and dump layout to "root.layout"

metadata.create_signature(signer_alice)

metadata.dump("root.layout")

The signed layout will come in handy in the verification phase. Stay tuned..

Generate metadata links

Once we have defined and signed the supply chain layout, we can start executing the supply chain steps and record metadata of the actual steps carried out by the authorized functionaries (Bob or Carl), as specified in the layout.

First, we will take the role of the functionary Bob by using his private key, and perform the clone step on his behalf.

We use in-toto-run to wrap the git clone command, allowing in-toto to gather metadata about it:

in-toto-run --step-name clone --use-dsse --products demo-project/foo.py --signing-key bob -- git clone https://github.com/in-toto/demo-project.git

Afterward, we continue taking the role of Bob by modifying the source code and updating the version number:

in-toto-run --step-name update-version --use-dsse --products demo-project/foo.py --signing-key bob -- sed 's/v0/v1/' demo-project/foo.py

Finally, we take the role of the functionary Carl by using his private key, and package the source code as a tarball file:

in-toto-run --step-name package --use-dsse --materials demo-project/foo.py --products demo-project.tar.gz --signing-key carl -- tar --exclude ".git" -zcvf demo-project.tar.gz demo-project

For each in-toto-run command execution, in-toto performs the following:

- Hash the contents of the inputs and outputs.

- Add the hash together with other information to a metadata file.

- Sign the metadata with the functionary private key.

- Store everything to

step.[functionary_key_id].link.

Verifying the final product

Once the final product (the tarball file) is packaged, we can verify that it’s tamper-free using the in-toto-verify command, by additionally providing the project owner’s public key, the signed layout and the link metadata (.link files) inside the same directory where the final product resides:

in-toto-verify --layout root.layout --verification-keys alice.pub

Running the verification command will return:

The software product passed all verification.

Return value: 0

As we previously described in the verification pseudo-code, the in-toto-verify command will check that:

- The layout has not expired.

- Layout was signed with Alice’s private key.

- Each step in the layout was performed and signed by the authorized functionary.

- The recorded materials and products follow the artifact rules and

- The inspection of the artifact (using

untar) finds the expected products.

Compromising the Supply Chain

Now let’s simulate the attack: an attacker manages to hack into the build server and modifies source code after bumping the version file, just before the code is packaged:

We will simulate the attack by injecting a “malicious” code into a source code file:

echo something evil >> demo-project/foo.py

Carl assumed that this is the genuine code he got from Bob and unintentionally packages the tampered code using in-toto-run command:

in-toto-run --step-name package --use-dsse --materials demo-project/foo.py --products demo-project.tar.gz --signing-key carl -- tar --exclude ".git" -zcvf demo-project.tar.gz demo-project

Verifying the malicious product

Since we used in-toto across the supply chain steps, we can identify the compromise during the verification phase:

in-toto-verify --layout root.layout --verification-keys alice.pub

This time, in-toto will detect that the product foo.py from Bob’s update-version step was not used as material in Carl’s package step (the verified hashes won’t match) and therefore will fail verification and return a non-zero value.

(in-toto-verify) RuleVerificationError: 'DISALLOW *' matched the following artifacts: ['demo-project/foo.py']

Return value: 1

This example illustrated a basic scenario where in-toto safeguards various steps in the software supply chain. More complex software supply chains can be secured by applying the same method over a wider scope of steps.

This example illustrated a basic scenario where in-toto safeguards various steps in the software supply chain. More complex software supply chains can be secured by applying the same method over a wider scope of steps.

Summary

In this article, we uncovered many interesting approaches in software supply chain security, as we studied the threats